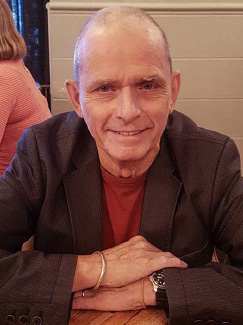

Sometimes a hobby comes in handy. Take Reinier Kreutzkamp, lecturer at the Faculty of Psychology and Neuroscience, who trains students in clinical skills. A cinephile since childhood, he also develops audiovisual material for training courses, including an innovative program called Dealing with Extreme Emotions. The video role plays using TrainTool software teach students to deal with real-life situations in a professional manner.

Lecturer faculty of Psychology and Neuroscience

Reinier Kreutzkamp

The program revolves around managing stress and extreme emotions in situations borrowed from clinical reality. What started out as pioneering work won the International E-Learning Award 2021. “Back in the early 1990s, when I left the clinic to focus on education,

I started making pedagogical films,” says Reinier Kreutzkamp, who works at the Department of Clinical Psychological Science. “In the last few years my faith in the educational value of film has really borne out.”

“Yes, it’s a bit like a flight simulator using films,” he says from his office, where the comparison is put to him. “It’s an interactive program that puts students in stressful situations. They learn to stay in control and respond professionally, even when the patient reacts emotionally and the situation turns threatening.

To stay with the flight simulator comparison, try putting a plane safely on the ground when an engine has failed, the fuel is about to run out and the weather’s not cooperating. Training in these situations ensures that you as a professional are prepared for emergencies.

The special thing about TrainTool is that the students record themselves with their phone, computer or tablet and can practise until they’re satisfied. And they receive feedback from fellow students and a teacher, so they also learn from one another.”

Anyone watching the films—including those in which Kreutzkamp himself plays the psychologist—immedi- ately grasps the difficulty and delicacy of the situation. In one, a ‘client’ with a history of domestic violence refuses to cooperate with a psychological test. All at once the actor ramps up the tension, making ugly accusations and gesticulating wildly. Kreutzkamp remains calm and in conversation with the person.

“In terms of emotions, we want to depict standard situations. As a professional, you have no choice but to continue with your test. At some point you’ll inevitably come across situations like this.”

Kreutzkamp’s clinical experience stretches all the way back to his childhood. Although his accent suggests otherwise, he was born and raised in Heerlen, near the Welterhof psychiatric centre (now Mondriaan), where his father was a psychiatrist.

Reinier Kreutzkamp is a lecturer in the Depart- ment of Clinical Psycho- logical Science at the Faculty of Psychology and Neuroscience at Maastricht University. He studied Personality Theory and Clinical Psychology at Utrecht University. Between 1981 and 1992 he also worked as a behavioural therapist at the Academic Anxiety Centre in Maastricht.

Reinier Kreutzkamp is a lecturer in the Depart- ment of Clinical Psycho- logical Science at the Faculty of Psychology and Neuroscience at Maastricht University. He studied Personality Theory and Clinical Psychology at Utrecht University. Between 1981 and 1992 he also worked as a behavioural therapist at the Academic Anxiety Centre in Maastricht.

Telling stories in pictures never gets boring.

“I’ve been going there all my life. We often celebrated Christmas there, together with the patients. I worked there during the holidays. I basically grew up surround- ed by psychiatric patients and professional caregivers. So it wasn’t a great leap, deciding to study psychology in Utrecht. After I graduated I moved to Maastricht University and have had the same employer for 40 years now. Never regretted a day.”

“In 2015,” he continues, “we started working with this innovative program, TrainTool, figuring we could use it to give students exactly what we thought they needed: practical experience in a setting indistinguishable from reality. Besides its pedagogical advantages, TrainTool enables us to reach more students and to save time. It’s an efficient and imaginative approach, very much in line with the current zeitgeist.”

Kreutzkamp emphasises that it is a team effort, together with faculty colleagues and the specialists from TrainTool. The conversation is shot through with his enthusiasm for the cinematic method. For someone who has always sought out academic challenges, it comes as no surprise that after his impending retire- ment he has no intention of sitting around twiddling his thumbs. “I plan to take a screenwriting course in Hasselt; I’m looking forward to that. I’ve enjoyed filming since I was a kid. Telling stories in pictures never gets boring. I’m fascinated by semiotics: the meaning of images.”

Which movies most appeal to him? “Obviously I’m fascinated by psychological themes. The often surrealistic images in old films—the French New Wave from the 50s and 60s by directors like Truffaut, Godard and Buñuel—really capture my imagination. Those films have many layers of meaning; they captivate me to this day. When it comes to films featuring a pathological state of mind, I find psychosis, with its perceptual disturbances and private realities, the most interesting. A Beautiful Mind, which explores the line between genius and madness, is just fantastic. Good films, including in their pedagogical application, have the power to touch people, move them, shed light on the other. Insight, understanding and empathy are important qualities, both in life and in my work.”